On November 3, 2021, Congress introduced a working draft of H.R.5376, the Build Back Better Act (BBB).1 This legislation would result in, among other things, major changes to the Medicare Parts B and D programs that could materially impact all stakeholders. The House passed this legislation on November 19, 2021, and the Senate is expected to vote in the coming weeks. Commentary in this paper is based on the Rules Committee Print 117-18 of November 3, 20221, while incorporating changes from the Rules Committee Amendment 117-19 of November 5, 2021.2 The key provisions affecting the Part D program and Medicare Part B drug reimbursement include:

- Allowing the federal government to negotiate prices for a subset of Part B and Part D drugs.

- Redesigning the Part D benefit design, including changes to the benefit phases as well as the responsibilities of each stakeholder within phases.

- Requiring drug manufacturers to pay rebates to the federal government if prices increase faster than inflation.

- Delaying the Part D point-of-sale (POS) rebate rule indefinitely.3

This Milliman brief provides an overview of these proposed changes. Although the BBB includes changes that affect other parts of the healthcare system, this Milliman brief focuses on impacts to Medicare Part D and Medicare Part B drug costs, summarizing the provisions as stated in the text. It does not attempt to outline considerations and questions. Milliman intends to publish additional pieces in the coming months discussing the implications of this legislation on the Medicare Advantage and Part D programs.

Drug price negotiation

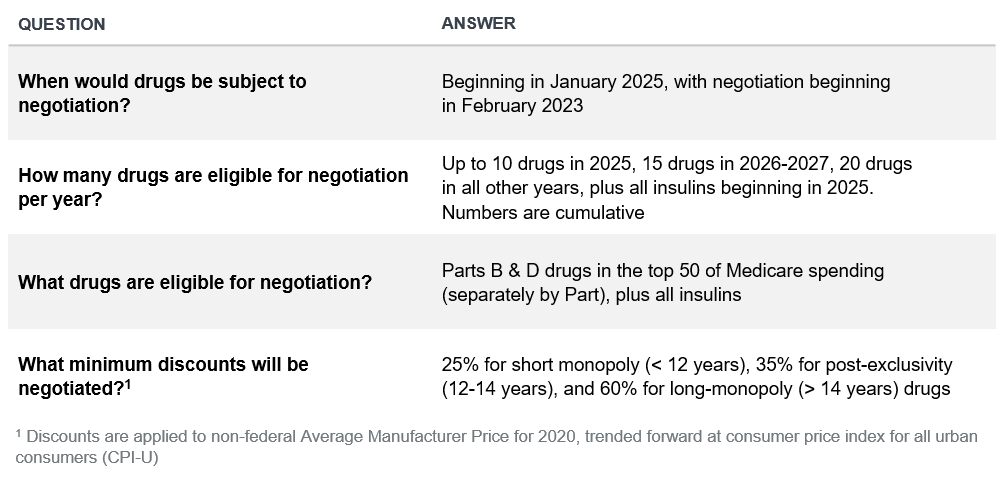

The BBB establishes a drug price negotiation program that allows the Secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to select a subset of Medicare Part B and D drugs beginning in 2025 to be subject to price negotiations with HHS, focused on drugs with the highest total expenditures and on insulin products. Drugs would be selected from the top 50 highest-spend qualifying single source Part B drugs, the 50 highest-spend qualifying single source Part D drugs, and single-source insulins. Figure 1 summarizes some common questions and answers about drug price negotiation.

Figure 1: Summary of key questions for drug price negotiation

Figure 2 illustrates the key dates for the first year that negotiated prices would be available (2025).

Figure 2: 2025 maximum fair price (MFP) negotiation timeline

Subsequent years are set to have the same windows of time dedicated to negotiation. The initial offer from the HHS Secretary is required to be delivered to the manufacturer by June 1, or 19 months prior to the negotiated price’s effective date. Manufacturers must respond to the offers from the Secretary within 30 days of receipt. As Figure 2 illustrates, plan sponsors would have about six months of lead time to incorporate negotiated prices into their bids, as the 2025 bids would be filed in June of 2024.

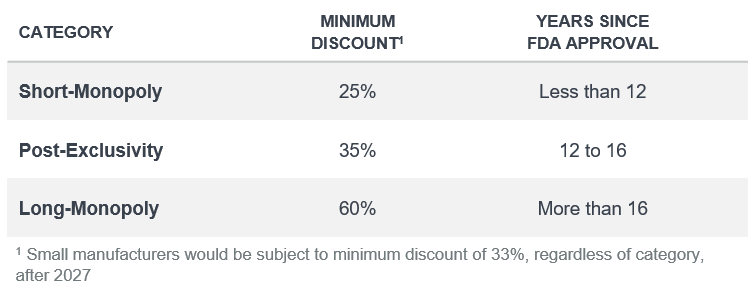

The number of newly selected drugs for negotiation would begin with 10 selected drugs in 2025, increasing by 15 each for 2026 and 2027, with 20 drugs selected in subsequent years. The number of negotiation-eligible drugs are cumulative. For example, this would allow the HHS Secretary to select 25 total drugs in 2026, though drugs may be removed from the list of negotiated drugs once competition enters the market. The Secretary may choose to negotiate any number of single-source insulins in addition to the number of drugs previously described. All selected drugs would be subject to a minimum discount aligned with the years since approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Figure 3 summarizes types outlined in the draft bill.

Figure 3: Types of negotiated drugs

The minimum discounts shown in Figure 3 are relative to the non-federal average manufacturer price (AMP) in 2020, indexed to the applicable year when the negotiated drug prices will be available.

In addition to the classifications above, small-molecule drugs would be eligible nine years after launch, while biologics would be eligible after 13 years. Additionally, there are several types of drugs that will be exempt from negotiations or have nonstandard treatment for a short period of time. These exceptions include:

- Orphan drugs, as defined under section 526 of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act.

- Low-spend Medicare drugs, defined as drugs with less than $200 million in expenditures in 2021, with the $200 million threshold indexed by the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U).

- Drugs manufactured by “Small Biotech” companies would be exempt from negotiation through 2027. This includes manufacturers whose portfolios account for less than 1% of expenditures in Part B or D and where a single drug comprises 80% of the manufacturer’s associated expenditures within Part B or D. Additionally, in 2028 and 2029, “Small Biotech” manufacturers will have a minimum discount of 33%, regardless of the status of their drugs, as described in Figure 3.

Manufacturers would pay 10 times the difference in actual and negotiated price, per unit dispensed, for failure to provide eligible entities the maximum fair price during the period of a maximum fair price agreement. A manufacturer of a selected drug that declines to sign an agreement when a selected drug is published will pay a variable tax that starts at two times the daily sales in the first 90 days of the year and grows to 19 times the daily sales in the last quarter of the year.

Part D benefit redesign

Benefit costs in the Part D program are paid by several stakeholders, described below. The amount covered by each stakeholder changes as the beneficiary moves through the benefit thresholds. The current stakeholders are:

- The federal government covers 80% of costs over the catastrophic threshold through the federal reinsurance program. Additionally, the government subsidizes premiums and cost sharing for low-income (LI) beneficiaries and pays a portion of program costs for all beneficiaries through risk-adjusted direct subsidy payments.

- Beneficiaries pay cost sharing and member premiums.

- Pharmaceutical manufacturers cover 70% of ingredient costs for certain drugs in the coverage-gap phase for non-low-income (NLI) beneficiaries.

- Plan sponsors estimate stakeholder costs through the bid process and are at risk for costs that exceed projections.

While there have been changes to the program over the years, Section 139201 of the BBB proposes the most significant changes to the structure of the benefit design to date, which will alter the financial responsibilities of all stakeholders.

Current benefit design

Under the current law, the Part D benefit design is as follows:

- Deductible: Beneficiaries pay 100% of costs ($480 in 2022).

- Initial coverage limit (ICL): Beneficiaries pay 25% of costs, plans pay 75% up to ICL ($4,430 in 2022).

- Coverage gap: NLI beneficiaries pay 25% of drug costs, manufacturers pay 70% of ingredient costs for applicable (brand) drugs, and plan sponsors pay 5% and 75% for applicable (brand) and nonapplicable (generic) drugs, respectively. For LI beneficiaries, the member and the low-income cost-sharing (LICS) subsidy cover 100% of drug costs.

- Catastrophic: The federal government pays 80% through reinsurance, the member pays 5%, and the plan pays 15% of drug costs.

An illustration of the current benefit design can be seen in Figure 4. Note that this reflects the defined standard design, and plans can modify member cost sharing in all phases to enhance the benefit.

Figure 4: Visual of 2022 Part D benefit design by stakeholder

Proposed new benefit design

Under the proposed benefit redesign, the Part D benefit would change as follows, effective January 1, 2024:

- Federal reinsurance would be changed from 80% for all drugs to 40% for nonapplicable (typically generic) drugs and 20% for applicable (typically brand) drugs.

- The coverage gap phase, along with the Coverage Gap Discount Program (CGDP), would be eliminated. Manufacturers would still be responsible for a portion of costs under a new program described in bullets #4 and #5 below.

- A new maximum out-of-pocket (MOOP) of $2,000 would be enacted. Beneficiaries would no longer be responsible for any costs above this MOOP. Along with #2 above, this would result in the benefit design moving from the current four phases (deductible, initial coverage phase, coverage gap, and catastrophic) to three phases (deductible, initial coverage phase, and catastrophic).

- A new pharmaceutical manufacturer discount program would be enacted in the initial coverage and catastrophic phases.

- Under the new program, manufacturers would cover 10% of costs above the deductible and under the MOOP.

- Above the MOOP, manufacturers would be responsible for 20% of costs.

- Unlike the CGDP, manufacturer liability would not accumulate toward a beneficiary’s MOOP.

- This new program would not apply to drugs subject to the drug price negotiation provisions of the BBB.

- Additionally, specified small manufacturers, defined in the phase-in section below, would have their liability phased in over time.

- Under the new manufacturer discount program, low-income (LI) beneficiaries would be included, unlike under the current CGDP. There would be a phase-in of this program for small drug manufacturers and specific manufacturers for LI beneficiaries, as described in the next section.

- Beneficiary cost sharing above the deductible and below the MOOP would be reduced from 25% to 23%.

- Cost sharing for insulin products would be capped at $35 per month for all plans (beginning on January 1, 2023).

- Beneficiaries with high cost-sharing liability would be able to spread their cost sharing evenly throughout the year rather than having to front-load it early in the year (begins on January 1, 2025).

An illustration of the new benefit design can be seen in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Illustration of proposed BBB Part D benefit design by stakeholder

Phase-in of new manufacturer discount program

The BBB includes a phase-in of the new manufacturer discount program for LI beneficiaries taking drugs from “specified” manufacturers and for all beneficiaries taking drugs from “specified small” drug manufacturers. The phase-in percentages would apply as follows:

- For costs under the MOOP, the manufacturer liability would start at 1% in 2024, then increase to 2% in 2025, 5% in 2026, 8% in 2027, and 10% in 2028 and later.

- For costs over the MOOP, the manufacturer liability would follow the same increases as the costs under the MOOP in (1) and then increase to 15% in 2029 and 20% in 2030 and later.

Figure 6 summarizes the different manufacturer types and beneficiaries where this phase-in would apply. Manufacturers are defined as “specified” or “specified small” as follows:

- A “specified” manufacturer is defined as a manufacturer where Medicare’s associated expenditures for all of the manufacturer’s drugs account for less than 1% of all expenditures in Part D or Part B. These drugs would be phased in for LIS beneficiaries only.

- A “specified small” manufacturer is defined as a manufacturer that qualifies as a “specified” manufacturer and also has one drug where the total expenditures for that drug under Part D or Part B account for more than 80% of the expenditures for all drugs for that manufacturer. These drugs would be phased in for all beneficiaries.

Figure 6: Phase-in for new pharmaceutical manufacturer discount program

National average member premium calculation

In addition to the changes described above, the BBB would change the calculation of the national average member premium (NAMP), affecting the direct subsidy. Currently, the NAMP is calculated at 25.5% of the total costs of the Part D program (national average bid amount + national average federal reinsurance amount). Under the BBB, the NAMP would be calculated as 23.5% of the total costs, thereby increasing the direct subsidy and lowering member premiums, all else equal.

Inflation rebates

The BBB introduces new rebate payments from manufacturers to the federal government if drug prices increase by more than inflation. Drug prices from the benchmark year (2021) are trended by CPI-U and compared to actual prices to calculate the inflation rebate. The rebate calculation varies between drugs covered by Medicare Parts B and D but follows a similar formula:

Inflation Rebate=Total Units*Max(Actual Price-Inflation Adjusted Benchmark,0)

Figure 7 illustrates the inflation rebate dynamics. A few additional highlights:

- Inflation rebates would apply to all drugs covered by Medicare Parts B and D, and would extend to the commercial market (e.g., employer self-funded, employer fully insured, individual) by using total units that include these markets.

- Manufacturers would be required to pay the inflation rebate within 30 days or be subject to a civil monetary penalty equal to 125% of the calculated inflation rebate.

- Rebate payments, regardless of source (Medicare vs. commercial), would be deposited directly to the Parts B and D Trust Funds.

Figure 7: Illustration of inflation rebate dynamic (assuming $1,000 drug price, 10% actual price increase, and 1% CPI-U)

Figure 8 summarizes key components of the inflation rebate calculations for Medicare Part B versus Part D drugs. We summarize additional detail by component in each section below.

Figure 8: Summary of key questions for inflation rebates (Part B vs. Part D drugs)

Medicare Part B drugs

Inflation rebates would apply to all single-source and biologic Medicare Part B drugs (including biosimilars), excluding vaccines and drugs that cost less than $100 per beneficiary per year. The key components include:

- The cost basis would reflect 106% of the average sales price (ASP) for the specific quarter, the typical Part B reimbursement.

- Inflation-adjusted payment amount would reflect the benchmark year manufacturer price (defined as cost during the quarter starting July 1, 2021, or upon launch), trended by CPI-U to the applicable quarter.

- Utilization would reflect total units for each National Drug Code (NDC) reported with ASP, less any units under Medicaid (Title XIX).

In Part B, member coinsurance is defined as 20% of allowable costs. This coinsurance would apply to the inflation-adjusted payment amount (benchmark cost trended by CPI-U) instead of 106% of ASP if an inflation rebate applies. This effectively passes a portion of the inflation rebate through to the beneficiary.

Figure 9 illustrates the timeline for the Part B inflation rebate calculation for a drug that has launched prior to September 2021. The first quarter eligible for rebates would start July 2023. The inflation-adjusted benchmark amount (from Q3 2021) would be adjusted by the change in CPI-U from September 2021 to six months prior to the current quarter (or January 2023, in this example). The HHS Secretary would calculate the rebate, notify the manufacturer within six months (or by January 1, 2024, in this example), and then the manufacturer would have 30 days to make the payment (or by February 1, 2024, in this example).

Figure 9: Part B inflation rebate timeline

For a drug that launches after September 2021, the following adjustments are made:

- Benchmark period CPI-U: Changes to the first month of the first full quarter following the drug launch.

- Payment benchmark period: Changes to third full calendar quarter following the drug launch.

- Inflation rebate start date: Changes to the sixth full calendar quarter following the drug launch.

Part B inflation rebates would be determined separately each quarter, with the six-month lookback. Within six months of the initial applicability (e.g., by January 1, 2024, for the July 1, 2023, quarter), the HHS Secretary would notify drug manufacturers of any inflation rebate owed for the quarter six months prior.

For both Parts B and D drugs, the inflation rebate would be waived for particular drugs if there is a material supply shortage, as determined by the HHS Secretary. The inflation rebate would also be excluded from the definitions of best price and AMP.

Medicare Part D drugs

Inflation rebates would also apply to all Medicare Part D or outpatient pharmacy drugs starting in 2023. The approach would be similar to the Medicare Part B drugs, with a few changes:

- The cost basis would reflect AMP. A weighted average AMP would be computed based on the relative units and AMP in each quarter of a particular year.

- Inflation-adjusted payment amount relies on the AMP for the year beginning September 1, 2021. The weighted average 2021 AMP (calculated the same way as the cost noted above) would be trended by CPI-U from September 2021 to January of each applicable year.

- Utilization would reflect all units relied on for the AMP calculation, less any Medicaid utilization.

For Part D drugs, the HHS Secretary will notify the manufacturer of an inflation rebate owed no later than nine months after the end of the plan year. This timing is similar to the reconciliation of other Part D items (e.g., federal reinsurance, risk corridors). The Secretary has the option to delay the reporting to manufacturers for the 2023 payment year by up to one year (to September 30, 2025).

Other changes

Other key changes proposed in the Build Back Better Act include:

- Point-of-sale (POS) rebates: The BBB would indefinitely delay enforcement of the point-of-sale rebate rule.4 This final rule, originally published in November 2020, would have removed the safe harbor protection for manufacturer rebates under the federal anti-kickback statute, thereby eliminating the current rebate program and requiring any rebate payments to be passed through to consumers at the point of sale.

- Expanding hearing coverage in Medicare: The BBB would expand Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) to cover hearing services, including hearing aids, starting in 2023. This would limit hearing aid coverage to no more than once per year over a five-year period. Notably, the BBB would not expand Medicare to cover dental and vision, two provisions that were considered during the legislative process.

- No cost sharing for Part D vaccines: Staring in 2024, plan sponsors would be required to offer vaccines at no cost sharing to Part D beneficiaries. This would occur regardless what phase of the benefit a beneficiary is in (e.g., the deductible would not apply).

- Biosimilar reimbursement changes: For a temporary five-year period (April 1, 2022, to March 31, 2027), Medicare Part B reimbursement for biosimilars would increase from 106% of ASP to 108% of ASP.

Next steps

As currently constituted, the BBB could drive some of the most material changes in drug pricing in the history of the Medicare Parts B and D programs. The changes are sweeping, with potential for some—such as inflation rebates—to be implemented as soon as 2023. The legislation is not final but is important to keep an eye on as changes develop.

There are many questions and considerations these changes may raise, and Milliman intends to publish additional pieces discussing the implications of these significant changes to the Medicare Advantage and Part D programs. In the meantime, if you have any questions on these changes or would like to discuss the potential impact on your business, please contact your Milliman consultant.

1 The full text is available at https://rules.house.gov/sites/democrats.rules.house.gov/files/BILLS-117HR5376RH-RCP117-18.pdf.

2 The full text of the amendment is available at https://amendments-rules.house.gov/amendments/YARMUT_024_xml211104220514322.pdf.

3 See https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/11/30/2020-25841/fraud-and-abuse-removal-of-safe-harbor-protection-for-rebates-involving-prescription-pharmaceuticals.

4 See https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/11/30/2020-25841/fraud-and-abuse-removal-of-safe-harbor-protection-for-rebates-involving-prescription-pharmaceuticals..